Black people and Native Americans are under-represented in Cancer Drug trials of new drugs

Black people and Native Americans are under-represented in clinical trials of new drugs, even when the treatment is aimed at a type of cancer that disproportionately affects them.

- Researchers found that clinical trials conducted largely outside the United States were much less likely to enroll Black participants.

- On average, non-U.S. trials enrolled less than half the proportion of Black patients.

- Experts say that study researchers can take several steps to boost black enrollment participation in clinical trials by building trust levels in that community.

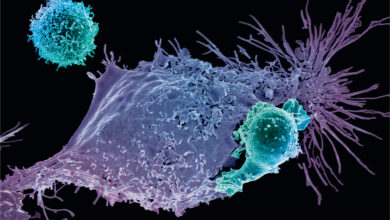

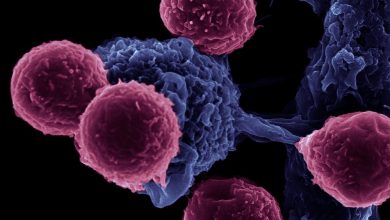

The racial disparity in cancer drug trials are not uncommon. Low participation rates of Black participants in clinical trials has long been an issue for researchers. Over these years, there is widespread under-representation of African Americans and Native Americans in clinical trials for cancer drugs, even when the type of cancer disproportionately affects them. This is partly due to the fact that FDA, the agency responsible for new drug approvals, has been reluctant to force drugmakers to enroll more minority patients, and the failure of most manufacturers to do so voluntarily, Recent data by the FDA indicates that fewer than 5 percent of the patients were black in trials for 24 of the 31 cancer drugs approved since 2015 although African-Americans make up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population.

Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; National Cancer Institute

Globalization impact on clinical trials

Pharmaceutical companies and research centers have been moving a significant number of drug clinical trials overseas in recent years to cut down the costs and speed up the drug approvals. Such globalization of cancer clinical trials is associated with a widening racial enrollment disparity gap in the United States. widening racial disparities in cancer clinical trials, according to a new study published online this month in Cancer, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society. The study was led by a team of researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, including Matthew Galsky, a professor of medicine specializing in oncology and hematology, and Serena Tharakan, a third-year medical student.

Similarly, other recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, found that among 61,763 overall participants, African-American representation was only 7.44%. Samer Al Hadidi, MD, MS, of Baylor College of Medicine, a lead author of this study mentioned that factors impeding representational participation among Blacks in cancer clinical trials include distrust of the medical system and bias against African Americans by those running such trials, as well as socioeconomic factors.

Expansion of trials for new drug applications abroad “broadens the already existing gap in racial disparities in patient enrollment in cancer clinical trials,” said Gail Trauco, a registered nurse and clinical research consultant based in the Atlanta area. The popular destinations for conducting such drug trials are Canada, Australia, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Israel — nations where the population is overwhelmingly white. “The goal of a trial should be to inform about the efficacy of a drug,” said Tharakan, noting that generalization is important when doing trials or it might be difficult to speak to potential side effects for a subset of the population. “It might be applicable for a certain population but not the whole population.”

“Diversity within clinical trials is important for a number or reasons,” said Sanjeev Luther, president and CEO of Rafael Pharmaceuticals, an East Windsor, New Jersey-based company specializing in cancer therapies. “The findings can be skewed or non-encompassing of an entire population as a result of the lack of diversity, resulting in an incomplete understanding of drug safety and efficacy.” He continued, “Diversity is important in studying cancer, orphan, and rare diseases because they are difficult to treat, but all conditions require the lens of inclusivity because they can affect all parts of our communities.”

What it means for the efficacy of drug in people of color

Recent study raises concerns about the generalization of the efficacy of the drugs developed during these trials. Without more Black participants the authors question whether or not the findings about the efficacy and safety of cancer drugs will hold for people of color.

What can be done

Dr. Rajbir Singh, an internal medicine specialist and director of clinical and translational research at Meharry College of Medicine, a historically black medical school in Nashville, called the study groundbreaking. “This is a good study. It hasn’t been done before,” he said, adding that more studies of this nature are needed and that future studies should consider looking at data from 2018 to 2020 as well. Singh said researchers could take several steps to boost Black enrollment participation in clinical trials by building trust levels in that community. This could involve doing more to educate the community about ethical practices and safeguards in clinical trials, and advertising on social media platforms and television.

He said the healthcare industry should work at developing more Black physicians and researchers to help raise trust levels in that community. He said researchers should consider taking the trials to the community as part of the education process. “There should be community advisory boards looking at how trials are presented to the community,” he said. “There should be patient stakeholder meetings talking how about how trials can help them and how they work.” In addition, researchers should consider assisting black participants with transportation to trial sites as well as compensating them when they miss work.

Diversity in clinical trials is important to ensure that drugs meet patients’ needs. The issue “is not elevated high enough in the discussion on clinical studies,” said John Maraganore, chair of the industry group Biotechnology Innovation Organization. But he added that enrolling minorities is challenging, often for reasons beyond the manufacturer’s control, and that it would require a “public-private partnership, working with the FDA and NIH [National Institutes of Health].”

Not enrolling in clinical trials is just one of many ways that African Americans trail white Americans in the quality of their health care. From diagnosis to death, they often experience inferior care and worse outcomes. Because some black Americans can’t afford the health insurance mandated under the Affordable Care Act, they remain less likely to have coverage than non-Hispanic white Americans.

There appear to be gaps in participation of other minority groups as well. Asians were well represented in trials held in some foreign countries, but they made up only 1.7 percent of patients for drugs for which at least 70 percent of trials were conducted within the U.S. By comparison, about 6 percent of the U.S. population identifies as Asian. Almost two-thirds of the trials didn’t report any Native Americans or Alaska Natives, who together make up about 2 percent of the U.S. population. ProPublica’s analysis excluded Hispanics, because the FDA reports did not have a separate category for them until 2017 and do not distinguish between white and non-white Hispanics.

The very relationship of race to drug development is fraught with controversy. Race is primarily seen as a social concept, rather than as a product of measurable biological traits. Yet there’s growing evidence that, whether for environmental or genetic reasons, drugs may have different effects on different populations.

Inadequate minority representation in drug trials means that “we aren’t doing good science,” said Dr. Jonathan Jackson, founding director of the Community Access, Recruitment and Engagement Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “If we aren’t doing good science and releasing these drugs out into the public, then we are at best being inefficient, at worst being irresponsible.

Diversity Trade-offs

Well, Diversity has its trade-offs too. Clinical trials already cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and drugmakers say that requiring participants to be racially representative would likely add more time and expense. “If you have a significant delay in enrollment, that would delay the medication advancing to the whole patient population, hurting everybody including the black population,” said Maraganore, who is also CEO of drugmaker Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc.

To offset costs caused by these delays, manufacturers might reduce the number of drugs in development, depriving some patients of experimental treatments, or raise prices, which would translate into higher insurance premiums and make new drugs even less affordable for the uninsured. Maraganore favors improving diversity through patient education — “a carrot-based approach” — rather than government regulation.

Dr. Rachel Sherman, the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, said that she’s “not entirely satisfied” with minority enrollment but that clinical trials have become more diverse in other ways. Two decades ago, women and children were rarely included in drug studies. Now those groups are better represented and the FDA is working on including more minorities, she said.

The globalization of cancer clinical trials may have the unintended consequence of further exacerbating existing racial disparities in cancer clinical trial representation and ultimately the generalizability of trial results. The impact of global trials on domestic clinical trial generalizability warrants further consideration from a regulatory and policy standpoint.